Leaders and Managers

Leaders and Managers

Leaders and Managers

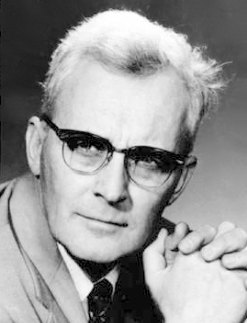

By Hugh W. Nibley

BYU Professor

BYU Commencement – August, 1983

Twenty-three years ago on this same occasion, I gave the opening prayer, in which I said: “We have met here today clothed in the black robes of a false priesthood.” Many have asked me since whether I really said such a shocking thing, but nobody has ever asked what I meant by it. Why not? Well, some knew the answer already, and as for the rest, we do not question things at the BYU. But for my own relief, I welcome this opportunity to explain: a “false priesthood?”

Why a priesthood? Because these robes originally denoted those who had taken clerical orders, and a college was a “mystery” with all the rites, secrets, oaths, degrees, tests, feasts, and solemnities that go with initiation into higher knowledge.But why false? Because it is borrowed finery, coming down to us through a long line of unauthorized imitators. It was not until 1893 that “an intercollegiate commission was formed to draft a uniform code for caps, gowns, and hoods” in the United States. Before that there were no rules—you designed your own; and that liberty goes as far back as these fixings can be traced. The late Roman emperors, as we learn from the infallible Du Cange, marked each step in the decline of their power and glory by the addition of some new ornament to the resplendent vestments that proclaimed their sacred office and dominion. Branching off from them, the kings of the tribes who inherited the lands and the claims of the Empire vied with each other in imitating the Roman masters, determined to surpass even them in the theatrical variety and richness of caps and gowns.One of the four crowns worn by the emperor was the mortarboard. The French kings got it from Charlemagne, the model and founder of their royal lines. To quote Du Cange:

When the French kings quitted the palace at Paris to erect a Temple of Justice, at the same time they conferred their royal adornments on those who would preside therein, so that the judgments that came from their mouths would have more weight and authority with the people, as if they were coming from the mouth of the prince himself [the idea of the Robe of the Prophet, conferring his glory on his successor]. It is to these concessions that the mortar-boards and the scarlet and ermine robes of the chancellors of France and the presidents of Parlement are to be traced. Their gowns or epitogia [the loose robe thrown over the rest of the clothing, to produce the well-known greenhouse effect], are still made in the ancient fashion. . . . The name “mortar-board” is given to the diadem because it is shaped like a mortar-board which serves for mixing plaster, and is bigger on top than on the bottom. [Charles Du Fresne, Sieur Du Cange, Glossarium ad Scriptores Mediae et Infimae Graecitatis (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck u. Verlagsanstalt, 1958; Unveränderter Abdruck der 1688 bei Anisson, Joan. Posuel u. Claud. Rigaud in Lyon erschiehenen Ausgabe)]

But where did the Roman emperors get it? For one thing, the mortarboard was called a Justinianeion, because of its use by the Emperor Justinian, who introduced it from the East. He got his court trappings and protocol from the monarchs of Asia, in particular the Grand Shah, from whom it can be traced to the khans of the steppes and the Mongol emperors, who wore the golden button of all wisdom on the top of the cap even as I do now; the shamans of the north also had it, and among the Laplanders it is still called “the Cap of the Four Winds.” The four-square headpiece topped by the golden tassel—”the emergent flame of Full Enlightenment”—also figures in some Buddhist and Lamaist representations. But you get the idea—this Prospero suit is pretty strong medicine—”rough magic” indeed! (See Shakespeare, The Tempest, act 5, scene 1, line 51.)

There is another type of robe and headdress described in Exodus and Leviticus and the third book of Josephus’ Antiquities, i.e., the white robe and linen cap of the Hebrew priesthood, which have close resemblance to some Egyptian vestments. They were given up entirely, however, with the passing of the temple, and were never even imitated again by the Jews. Both their basic white and their peculiar design, especially as shown in the latest studies from Israel, are much like our own temple garments. This is not the time or the place to pursue a subject in which Brother Packer wisely recommends a judicious restraint; I bring it up only to ask myself, “What if I appeared for an endowment session in the temple dressed in this outfit?” There would be something incongruous about it, of course, even comical. But why should that be so? The original idea behind both garments is the same—to provide a clothing more fitting to another ambience, action, and frame of mind than that of the warehouse, office, or farm. Section 109 of the Doctrine and Covenants describes the function and purpose of the temple as much the same as those of a university: a house where all seek learning by study and faith, by discriminating search among the best books (no official list is given), and by constant discussion—diligently teaching “one another words of wisdom”; everybody seeking greater light and knowledge as all things come to be “gathered in one”—hence university.

Both the black and the white robes proclaim a primary concern for things of the mind and the spirit, sobriety of life, and concentration of purpose removed from the largely mindless, mechanical routines of your everyday world. Cap and gown announced that the wearer had accepted certain rules of living and been tested in special kinds of knowledge.

What is wrong, then, with the flowing robes? For one thing, they are somewhat theatrical and too easily incline the wearer, beguiled by their splendor, to masquerade and affectation. In the time of Socrates the Sophists were making a big thing of their special manner of dress and delivery. It was all for show, of course, but it was “dressing for success” with a vengeance, for the whole purpose of the rhetorical brand of education which they inaugurated and sold at top prices to the ambitious youth was to make the student successful as a paid advocate in the law courts, a commanding figure in public assemblies, or a successful promoter of daring business enterprises by mastering those irresistible techniques of persuasion and salesmanship which the Sophists had to offer.

That was the classical education which Christianity embraced at the urging of the great St. Augustine. He had learned by hard experience that you can’t trust revelation because you can’t control it—the Spirit bloweth where it listeth, and what the Church needed was something more available and reliable than that, something, he says, commodior et multitudini tutior—”handier and more reliable for the public”—than revelation or even reason, and that is exactly what the rhetorical education had to offer.

At the beginning of this century scholars were strenuously debating the momentous transition from Geist to Amt, from Spirit to office, from inspiration to ceremony in the leadership of the Early Church, when the inspired leader was replaced by the typical city bishop, an appointed and elected official—ambitious, jealous, calculating, power-seeking, authoritarian; an able politician and a master of public relations—St. Augustine’s trained rhetorician. At the same time the charismatic gifts, the spiritual gifts, not to be trusted, were replaced by rites and ceremonies that could be timed and controlled, all following the Roman imperial model, as Alfoeldi has shown, including the caps and gowns.

And down through the centuries the robes have never failed to keep the public at a respectful distance, inspire a decent awe for the professions, and impart an air of solemnity and mystery that has been as good as money in the bank. The four faculties of Theology, Philosophy, Medicine, and Law have been the perennial seedbeds not only of professional wisdom, but of the quackery and venality so generously exposed to public view by Plato, Rabelais, Molière, Swift, Gibbon, A. E. Housman, H. L. Mencken, and others.

What took place in the Greco-Roman as in the Christian world was that fatal shift from leadership to management that marks the decline and fall of civilizations.

At the present time, Captain Grace Hopper, that grand old lady of the Navy, is calling our attention to the contrasting and conflicting natures of management and leadership. No one, she says, ever managed men into battle. She wants more emphasis in teaching leadership. But leadership can no more be taught than creativity or how to be a genius. The Generalstab tried desperately for a hundred years to train up a generation of leaders for the German army, but it never worked, because the men who delighted their superiors, i.e., the managers, got the high commands, while the men who delighted the lower ranks, i.e., the leaders, got reprimands. Leaders are movers and shakers, original, inventive, unpredictable, imaginative, full of surprises that discomfit the enemy in war and the main office in peace. For managers are safe, conservative, predictable, conforming organization men and team players, dedicated to the establishment.

The leader, for example, has a passion for equality. We think of great generals from David and Alexander on down, sharing their beans or maza with their men, calling them by their first names, marching along with them in the heat, sleeping on the ground, and first over the wall. A famous ode by a long-suffering Greek soldier, Archilochus, reminds us that the men in the ranks are not fooled for an instant by the executive type who thinks he is a leader.

For the manager, on the other hand, the idea of equality is repugnant and indeed counterproductive. Where promotion, perks, privilege, and power are the name of the game, awe and reverence for rank is everything, the inspiration and motivation of all good men. Where would management be without the inflexible paper processing, dress standards, attention to proper social, political, and religious affiliation, vigilant watch over habits and attitudes, and so forth, that gratify the stockholders and satisfy security?

“If you love me,” said the Greatest of all leaders, “you will keep my commandments.” “If you know what is good for me,” says the manager, “you will keep my commandments, and not make waves.” That is why the rise of management always marks the decline of culture. If the management does not go for Bach, very well, there will be no Bach in the meeting; if management favors vile, sentimental doggerel verse extolling the qualities that make for success, young people everywhere will be spouting long trade-journal jingles from the stand; if the management’s taste in art is what will sell—trite, insipid, folksy kitsch—that is what we will get; if management finds maudlin, saccharine commercials appealing, that is what the public will get; if management must reflect the corporate image in tasteless, trendy new buildings, down come the fine old pioneer monuments.

To Parkinson’s Law, which shows how management gobbles up everything else, he added what he calls the “Law of Injelitance”: Managers do not promote individuals whose competence might threaten their own position; and so as the power of management spreads ever wider, the quality deteriorates, if that is possible. In short, while management shuns equality, it feeds on mediocrity.

On the other hand, leadership is an escape from mediocrity. All the great deposits of art, science, and literature from the past on which all civilization is nourished come to us from a mere handful of leaders. For the qualities of leadership are the same in all fields, the leader being simply the one who sets the highest example; and to do that and open the way to greater light and knowledge, the leader must break the mold. “A ship in port is safe,” says Captain Hopper, speaking of management; “but that is not what ships were built for,” she adds, calling for leadership. True leaders are inspiring because they are inspired, caught up in a higher purpose, devoid of personal ambition, idealistic, and incorruptible.

There is necessarily some of the manager in every leader (what better example than Brigham Young?), as there should be some of the leader in every manager. Speaking in the temple to the temple management, the scribes and Pharisees all in their official robes, the Lord chided them for one-sidedness: They kept careful accounts of the most trivial sums brought into the temple, but in their dealings they neglected fair play, compassion, and good faith, which happen to be the prime qualities of leadership. The Lord insisted that both states of mind are necessary, and that is important: “This ye must do [speaking of the bookkeeping] but not neglect the other.” But it is “the blind leading the blind,” he continues, who reverse priorities, who “choke on a gnat and gulp down a camel” (see Matthew 23:23ff). So vast is the discrepancy between management and leadership that only a blind man would get them backwards. Yet that is what we do. In that same chapter of Matthew, the Lord tells the same men that they do not really take the temple seriously while the business contracts registered in the temple they take very seriously indeed (see Matthew 23:16-18). I am told of a meeting of very big businessmen in a distant place, who happened also to be the heads of stakes, where they addressed the problem of “how to stay awake in the temple.” For them what is done in the house of the Lord is mere quota-filling until they can get back to the real work of the world.

History abounds in dramatic confrontations between the two types, but none is more stirring than the epic story of the collision between Moroni and Amalickiah—the one the most charismatic leader, the other the most skillful manager in the Book of Mormon. We are often reminded that Moroni “did not delight in the shedding of blood” and would do anything to avoid it, repeatedly urging his people to make covenants of peace and preserve them by faith and prayer. He refused to talk about “the enemy”—for him they were always “our brethren,” misled by the traditions of their fathers; he fought them only with heavy reluctance, and he never invaded their lands, even when they threatened intimate invasion of his own; for he never felt threatened, since he trusted absolutely in the Lord. At the slightest sign of weakening by an enemy in battle, Moroni would instantly propose a discussion to put an end to the fighting. The idea of total victory was alien to him—no revenge, no punishment, no reprisals, no reparations, even for an aggressor who had ravaged his country. He would send the beaten enemy home after battle, accepting their word for good behavior or inviting them to settle on Nephite lands, even when he knew he was taking a risk. Even his countrymen who fought against him lost their lives only while opposing him on the field of battle—there were no firing squads, and former conspirators and traitors had only to agree to support his popular army to be reinstated. And, like Helaman, he insisted that conscientious objectors keep their oaths and not go to war even when he desperately needed their help. Always concerned with doing the decent thing, he would never take what he called unfair advantage of an enemy. Devoid of personal ambition, the moment the war was over he “yielded up the command of his armies . . . and he retired to his own house . . . in peace” (Alma 62:43), though as a national hero he could have had any office or honor. For his motto was, “I seek not for power,” and as to rank, he thought of himself only as one of the despised and outcast of Israel. If all this sounds a bit too idealistic, may I remind you that there really have been such men in history, hard as that is to imagine today.

Above all, Moroni was the charismatic leader, personally going about to rally the people, who came running together spontaneously to his “title of liberty,” the banner of the poor and downtrodden of Israel (Alma 46:12-13, 19-21). He had little patience with management and let himself get carried away and wrote tactless and angry letters to the big men sitting on their thrones “in a state of thoughtless stupor” back in the capital. And when it was necessary, he bypassed the whole system; he “altered the management of affairs among the Nephites,” to counter Amalickiah’s managerial skill (Alma 49:11; emphasis added). Yet he could apologize handsomely when he learned that he had been wrong, led by his generous impulses to an exaggerated contempt for management, and he gladly shared with Pahoran the glory of the final victory—the one thing that ambitious generals jealously reserve for themselves.

But if Moroni hated war so much, why was he such a dedicated general? He leaves us in no doubt on that head—he took up the sword only as a last resort: “I seek not for power, but to pull it down” (Alma 60:36). He was determined “to pull down their pride and their nobility”—the pride and nobility of those groups who were trying to take things over (Alma 51:17). The “Lamanite brethren” he fought were the reluctant auxiliaries of Zoramites and Amalickiahites, his own countrymen. They “grew proud . . . , because of their exceedingly great riches,” and sought to seize power for themselves (Alma 45:23ff). Enlisting the aid of “those who were in favor of kings . . . those of high birth . . . supported by those who sought power and authority over the people” (Alma 51:8), they were further joined by important judges who had many friends and kindreds (the right connections are everything) plus almost all the lawyers and the high priests, to which were added “the lower judges of the land, and they were seeking for power” (Alma 46:4). All these Amalickiah welded together with immense managerial skill to form a single ultraconservative coalition who agreed to “support him and establish him to be their king,” expecting that “he would make them rulers over the people” (Alma 46:5). Many in the church were won over by Amalickiah’s skillful oratory, for he was a charming flattering is the Book of Mormon word) and persuasive communicator. He made war the cornerstone of his policy and power, using a systematic and carefully planned communication system of towers and trained speakers to stir up the people to fight for their rights, meaning Amalickiah’s career. For while Moroni had kind feelings for the enemy, Amalickiah “did care not for the blood of his people” (Alma 49:10). His object in life was to become king of both the Nephites and Lamanites, using the one to subdue the other (see Alma 46:5). He was a master of dirty tricks, to which he owed some of his most brilliant achievements as he maintained his upward mobility by clever murders, high-powered public relations, and great executive ability. His competitive spirit was such that he swore to drink the blood of Alma, who stood in his way. In short, he was “one very wicked man” (Alma 46:9), who stood for everything that Moroni loathed.

It is at this time in Book of Mormon history that the word management makes its only appearances (three of them) in all the scriptures. First there was that time when Moroni on his own “altered the management of affairs among the Nephites” (Alma 49:11) during a crisis. Then there was Korihor, the ideological spokesman for the Zoramites and Amalickiahites, who preached that “every man fared in this life according to the management of the creature; therefore every man prospered according to his genius [ability, talent, brains, and so forth], and . . . conquered according to his strength; and whatsoever a man did was no crime” (Alma 30:17; emphasis added). He raged against the government for taking people’s property, that “they durst not make use of that which is their own” (Alma 30:28). Finally, as soon as Moroni disappeared from the scene, the old coalition “did obtain the sole management of the government,” and immediately did “turn their backs upon the poor” (Helaman 6:39; emphasis added), while they appointed judges to the bench who displayed the spirit of cooperation by “letting the guilty and the wicked go unpunished because of their money” (Helaman 7:5). (All this took place in Central America.)

Such was the management that Moroni opposed. By all means, brethren, let us take “Captain Moroni” for our model, and never forget what he fought for—the poor, outcast, and despised; and what he fought against—pride, power, wealth, and ambition; or how he fought, as the generous, considerate, and magnanimous foe—a leader in every sense.

(Even at the risk of running overtime I must pause and remind you that this story of which I have given just a few small excerpts is supposed to have been cooked up back in the 1820s somewhere in the backwoods by some abysmally ignorant, disgustingly lazy, and shockingly unprincipled hayseed. Aside from a light mitigation of those epithets, that is the only alternative to believing that the story is true; nobody made it up, for the situation is equally fantastic no matter what kind of author you choose to invent.)

That Joseph Smith is beyond compare the greatest leader of modern times is a proposition that needs no comment. Brigham Young recalled that many of the brethren considered themselves better managers than Joseph and were often upset by his economic naiveté. Brigham was certainly a better manager than the Prophet (or anybody else, for that matter), and he knew it, yet he always deferred to and unfailingly followed Brother Joseph all the way while urging others to do the same, because he knew only too well how small is the wisdom of men compared with the wisdom of God.

Moroni scolded the management for their “love of glory and the vain things of the world” (Alma 60:32), and we have been warned against the things of this world as recently as the last general conference. But exactly what are the things of the world? An easy and infallible test has been given us in the well-known maxim “You can have anything in this world for money.” If a thing is of this world, you can have it for money; if you cannot have it for money, it does not belong to this world. That is what makes the whole thing manageable—money is pure number; by converting all values to numbers, everything can be fed into the computer and handled with ease and efficiency. “How much?” becomes the only question we need to ask. The manager “knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing” (Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan, act 3), because for him the value is the price.

Look around you here. Do you see anything that cannot be had for money? Is there anything here you couldn’t have if you were rich enough? Well, for one thing you may think you detect intelligence, integrity, sobriety, zeal, character, and other such noble qualities—don’t the caps and gowns prove that? But hold on! I have always been taught that those are the very things that managers are looking for—they bring top prices in the marketplace. Does their value in this world mean, then, that they have no value in the other world? It means exactly that: such things have no price and command no salary in Zion; you cannot bargain with them because they are as common as the once-pure air around us; they are not negotiable in the kingdom because there everybody possesses all of them in full measure, and it would make as much sense to demand pay for having bones or skin as it would to collect a bonus for honesty or sobriety. It is only in our world that they are valued for their scarcity. “Thy money perish with thee,” said Peter to a gowned quack (Simon Magus), who sought to include “the gift of God” in a business transaction (see Acts 8:9-24).

The group leader of my high priests quorum is a solid and stalwart Latter-day Saint who was recently visited by a young returned missionary who came to sell him some insurance. Cashing in on his training in the mission field, the fellow assured the brother that he knew that he had the right policy for him just as he knew the gospel was true. Whereupon my friend, without further ado, ordered him out of the house. For one with a testimony should hold it sacred and not sell it for money. The early Christians called Christemporoi those who made merchandise of spiritual gifts or Church connections. The things of the world and the things of eternity cannot be thus conveniently conjoined, and it is because many people are finding this out today that I am constrained at this time to speak on this unpopular theme.

For the past year I have been assailed by a steady stream of visitors, phone calls, and letters from people agonizing over what might be called a change of major. Heretofore the trouble has been the repugnance the student (usually a graduate) has felt at entering one line of work when he or she would greatly prefer another. But what can they do? “If you leave my employ,” says the manager, “what will become of you?” But today it is not boredom or disillusionment, but conscience that raises the problem: To “seek ye first financial independence and all other things shall be added,” is recognized as a rank perversion of the scriptures and an immoral inversion of values.

To question that sovereign maxim, one need only consider what strenuous efforts of wit, will, and imagination have been required to defend it. I have never heard, for example, of artists, astronomers, naturalists, poets, athletes, musicians, scholars, or even politicians coming together in high-priced institutes, therapy groups, lecture series, outreach programs, or clinics to get themselves psyched up by GO! GO! GO! slogans, moralizing clichés, or the spiritual exercises of a careful dialectic, to give themselves what is called a “wealth mind-set” with the assurance that (in the words of Korihor) “whatsoever a man [does is] no crime” (Alma 30:17). Nor do those ancient disciplines lean upon lawyers, those managers of managers, to prove to the world that they are not cheating. Those who have something to give to humanity revel in their work and do not have to rationalize, advertise, or evangelize to make themselves feel good about what they are doing.

In my latest class a graduating honors student in business management wrote this—the assignment was to compare oneself with some character in the Pearl of Great Price, and he quite seriously chose Cain:

Many times I wonder if many of my desires are too self-centered. Cain was after personal gain. He knew the impact of his decision to kill Abel. Now, I do not ignore God and make murderous pacts with Satan; however, I desire to get gain. Unfortunately, my desire to succeed in business is not necessarily to help the Lord’s kingdom grow [a refreshing bit of honesty]. Maybe I am pessimistic, but I feel that few businessmen have actually dedicated themselves to the furthering of the church without first desiring personal gratification. As a business major, I wonder about the ethics of business—”charge as much as possible for a product which was made by someone else who was paid as little as possible. You live on the difference.” As a businessman will I be living on someone’s industry and not my own? Will I be contributing to society, or will I receive something for nothing, as did Cain? While being honest, these are difficult questions for me.

They have been made difficult by the rhetoric of our times. The Church was full of men in Paul’s day “supposing that gain is godliness” (1 Timothy 6:5) and making others believe it. Today the black robe puts the official stamp of approval on that very proposition. But don’t blame the College of Commerce! The Sophists, those shrewd businessmen and showmen, started that game 2,500 years ago, and you can’t blame others for wanting to get in on something so profitable. The learned doctors and masters have always known which side their bread was buttered on and have taken their place in the line. Business and “Independent Studies,” the latest of the latecomers, have filled the last gaps, and today, no matter what your bag, you can put in for a cap and gown. And be not alarmed that management is running the show—they always have.

Most of you are here today only because you believe that this charade will help you get ahead in the world. But in the last few years things have got out of hand; “the economy,” once the most important thing in our materialistic lives, has become the only thing. We have been swept up in a total dedication to “the economy,” which like the massive mud slides of our Wasatch Front, is rapidly engulfing and suffocating everything. If President Kimball is “frightened and appalled” by what he sees, I can do no better than to conclude with his words: “We must leave off the worship of modern-day idols and a reliance on the `arm of flesh,’ for the Lord has said to all the world in our day, `I will not spare any that remain in Babylon'” (“The False Gods We Worship,” Ensign, June 1976, p. 6). And Babylon is where we are.

In a forgotten time, before the Spirit was exchanged for the office and inspired leadership for ambitious management, these robes were designed to represent withdrawal from the things of this world—as the temple robes still do. That we may become more fully aware of the real significance of both is my prayer in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.